- ExoBrain weekly AI news

- Posts

- ExoBrain weekly AI news

ExoBrain weekly AI news

9th January 2026: Alien tools with no manual, capital in the AI century, and Nvidia flexes at CES

This week we look at:

Terminal AI agents, the “alien tools” that caught the imagination over the holidays

Capital in the AI century and why Piketty may be vindicated

Nvidia’s CES keynote and the $20 billion Groq acquisition

Alien tools with no manual

Welcome back, and Happy New Year! If 2025 was the cautious dawn of the agentic AI era, 2026 is already shaping up to be the year it arrives in force. In just the past two weeks, we’ve seen a frenzy of activity that has caught even seasoned AI folk off guard. The models and tools causing the excitement are not new, but holiday break experimentation allowed more people to realise that we may not be that far from AGI, at least for knowledge-based tasks.

The tools driving this change are terminal agents: AI systems that run in your “command line”, read and write files, execute code, browse the web, and chain actions together autonomously. The category leaders are Anthropic’s Claude Code, now almost entirely developed by Claude Code itself, and OpenAI’s Codex CLI. A growing ecosystem of model-agnostic alternatives like OpenCode, Aider, and Goose let users bring their own model, a GPT, Gemini, or local open-weight option. The common thread: these tools live where the work happens, with full access to your file system, git repositories, and development environment.

Claude Code 2.1, which shipped this week, illustrates how quickly the category is maturing. Skills, reusable workflows stored as text files that the agent loads when relevant, now hot-reload without restarts. Crucially, Claude can write and update its own skills during a session, a form of learning that persists across activities. Skills can now also breakout into isolated context windows, effectively spawning parallel agents that work independently without polluting the main thread. And for those who want to keep going beyond the terminal, the /teleport command lets you push a session to the cloud and pick it up on your phone via the Claude mobile app, turning a desktop coding session into something you can continue from anywhere.

Andrej Karpathy, the researcher who coined the term “vibe coding” back in February 2025, posted on December 26th with some candour: “I’ve never felt this much behind as a programmer. The profession is being dramatically refactored as the bits contributed by the programmer are increasingly sparse and between.” He described current AI coding tools as “some powerful alien tool handed around except it comes with no manual”, noting that “once in a while when you hold it just right a powerful beam of laser erupts and melts your problem.” But it also “shoots pellets” or “misfires”, highlighting the learning curve that makes mastery elusive. Karpathy sensed he could be “10X more powerful” if he properly strung together what had become available over the past year. A failure to claim the boost, he said, “feels decidedly like skill issue.”

Boris Cherny, the creator of Claude Code, responded with context that explains why veterans struggle: “It takes significant mental work to re-adjust to what the model can do every month or two, as models continue to become better and better at coding and engineering.” New graduates might actually have an advantage because “they don’t assume what AI can and cannot do”, meaning prior mental models become a handicap. Cherny’s own workflow illustrates where this leads: he runs five Claude instances simultaneously in numbered terminal tabs, using system notifications to know when each needs input, plus an additional five to ten on the web interface. That’s potentially fifteen agents running in parallel, producing 50 to 100 pull requests per week. His most striking claim: “In the last thirty days, 100% of my contributions to Claude Code were written by Claude Code.”

Google have also added to the Claude Code / Opus 4.5 hype, with a senior engineer posting: “I’m not joking and this isn’t funny. We have been trying to build distributed agent orchestrators at Google since last year. There are various options, not everyone is aligned… I gave Claude Code a description of the problem, it generated what we built last year in an hour.”

The “Ralph Wiggum Technique” also went viral in the final week of December. Named after The Simpsons character, it’s a deceptively simple approach created by Geoffrey Huntley: a loop that repeatedly feeds output as input to the AI agent until completion criteria are met. The insight is that iteration beats perfection. You define clear success criteria, let the agent work autonomously, and treat failures as data that refines the approach.

Perhaps the most significant community realisation from the Christmas break: Claude Code really is less about “coding” and more about being a general-purpose agent that happens to use code as its medium. Non-coders have used it for tax preparation, booking theatre tickets, automating grocery shopping via browser control, and managing smart homes through Home Assistant. Dan Shipper from Every captured the difference between web-based AI and terminal agents: “The cloud app is like a hotel room, clean and set up for you, but you start fresh each time. Claude Code is like having your own apartment with AI in it. You can customise it, build on it, and create something together over time.” The question is no longer “is this a coding task?” but “can this be done “digitally”?

Takeaways: Claude Opus 4.5, GPT-5.2, and Gemini 3 have quietly crossed an invisible threshold. These models can now sustain focus through longer autonomous sessions, chain tools reliably, and complete in minutes what previously took hours or days. The holiday break gave practitioners time to really put them to the test in the latest “harnesses”. Terminal agents are being shown to be general-purpose automation engines for digital tasks. Tax preparation, shopping, smart home management, research workflows: if it can be done on a computer, it can increasingly be delegated. But right now the tools are not friendly, mature, or easily accessible. The personal agent operating system is only available to those who can rig it up over the holiday break. But the alien technology has arrived and 2026 will be defined by how quickly we learn to operate it.

Capital in the AI century

Most discourse on AI economics these days looks at “will AI take my job?”, i.e. where will “capital substitute for labour”, and assumes automation is an incremental diffusion. Philip Trammell and Dwarkesh Patel’s “Capital in the 22nd Century”, one of the most thought provoking pieces published over the holiday break, goes further and farther and suggests that the AI capital winners could take all. Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century argued that without strong redistribution, inequality compounds indefinitely… the rich save more, earn higher returns, and pull ever further ahead. Critics challenge this as historically unsubstantiated and argue that capital and labour have been complementary. Trammell and Patel’s “Capital in the 22nd Century” (the title is no accident) is subtitled: “Piketty was wrong about the past, but AI will make him right about the future.”

Historically they argue, capital accumulation has been self-correcting as “more hammers” mean more demand for hands to use them, pushing wages up. But once AI can do everything humans can, this correction breaks. Returns accrue entirely to wealthy capital owners, and inequality compounds without limit. In our year-end analysis, we also identified “an imperative for capital capture rather than worker distribution” arising from the intensive up front AI investment model. We warned about “efficiency gains stranded in an economy with insufficient purchasing power” if automation outpaces adaptation. We noted the hidden displacement already underway: job losses, frozen hiring, and severed entry-level career paths creating a “silent iceberg” of workforce disruption.

We framed the challenge as adoption: 2026 is a tightrope between two existential risks, a disorderly unwinding of the productivity overhang triggering a job displacement crisis, or a persistent adoption lag exploding the debt-fuelled off-balance sheet bubble. We argued for “genuine human-machine teaming” so capital captures its necessary return without suffocating the economy. But Trammell and Patel describe a bigger risk: even after safely navigating this narrow path, the platform may be unstable. Our framing assumed complementarity, but the authors believe this will only be temporary. Full labour substitutability will lead to “Jevons world,” where capital accumulation no longer faces diminishing returns that historically raised wages; human-AI teaming will be transitional, not equilibrium.

The essay has drawn substantial pushback. Ben Thompson’s Stratechery rebuttal argues that human preferences for artisanal services, authentic experiences, and human connection could sustain labour’s share even in full automation. But will preferences alone preserve labour’s slice of the pie? In a world of genuine abundance, or one where AI-accelerated scientific progress reshapes what humans can do and want, the zero-sum distributional logic may not apply. Their model assumes we’re fighting over shares of a fixed or steadily growing output. What if the nature of value generation changes so fundamentally that “labour share” becomes the wrong question?

Zvi Mowshowitz, AI blogger, struggles with the fundamental assumptions of the analysis, that human institutions persist: property rights enforced, legal systems functioning, AIs serving human capital owners rather than accumulating for themselves. Why would any of that hold? He quotes Eliezer Yudkowsky: “What is with this huge, bizarre, and unflagged presumption that property rights, as assigned by human legal systems, are inviolable laws of physics? That ASIs remotely care?” In Mowshowitz’s and Yudkowsky’s world of artificial superintelligences, the question isn’t which humans own the capital, it’s whether human ownership means anything at all.

But the variable that perhaps matters most may be what we collectively decide to value in the future. The scarcity frontier will move to what AI cannot provide, which may be something we have yet to understand. Whether the correction of inequality can persist may depend more on our consumption choices than on the automation of production. The question isn’t just what AI will replace. It’s what we decide to want.

Takeaways: Trammell and Patel’s essay is worth reading because it asks the bigger questions and explores the more radical models most AI commentary avoids. But its title is misleading. It’s not about capital in the 22nd century, capital concentration dynamics are operating now. The practical question for 2026 is how we build for human-machine complementarity, not substitution, and create new scarcities where human contribution remains vital.

Nvidia flexes at CES

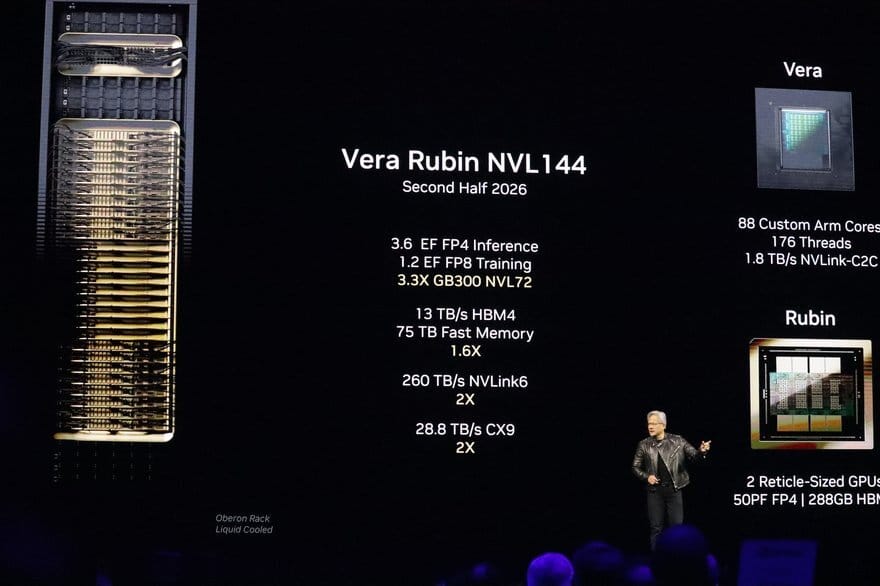

This image from Jensen Huang’s CES 2026 keynote shows the Vera Rubin NVL144, a liquid-cooled rack delivering 3.6 exaflops of FP4 inference in a single box. Nvidia launched the Rubin platform this week, and stated that production had started for delivery in H2, with the chip offering a 5x boost in inference performance over Blackwell and a 10x reduction in cost per token. Crucially it also offers a 1.6x improvement in terms of memory bandwidth. This matters because AI inference is increasingly bottlenecked not by calculations but by how quickly you can feed data to the processors. Nvidia’s $20 billion acquisition of Groq, announced just before CES, addresses the same problem from a different angle: Groq’s SRAM-based approach trades capacity for raw speed, achieving remarkable latency by keeping model weights on-chip, though this requires hundreds of chips working together to run even a modest 70 billion parameter model. But as Huang explained in a Q&A, today’s biggest challenge is workload diversity. Mixture-of-experts models, diffusion models, and state-space models all stress different parts of the system and need different hardware and software capabilities. Nvidia’s pitch is increasingly focused on flexibility: rather than optimise for one workload type, build infrastructure that adapts as the demands shift from morning to night. Nvidia’s aim is to be in the same dominant position this time next year no matter what the model architectures and use cases are (and how many TPUs Google are able to sell).

Weekly news roundup

This week's news highlights major corporate moves in AI adoption and acquisition, growing tensions around AI governance and transparency, fundamental research questioning scaling assumptions, and the intensifying race to secure energy and hardware infrastructure for AI systems.

AI business news

JPMorgan ditches proxy advisors and turns to AI for shareholder votes (Signals a significant shift in how major financial institutions are delegating complex decision-making to AI systems.)

Tailwind's shattered business model is a grim warning for every business relying on site visits in the AI era (A cautionary tale for businesses whose value proposition may be disrupted by AI-powered information retrieval.)

Meta's big Manus AI purchase hits a Chinese regulatory wall (Illustrates the geopolitical complexities now surrounding cross-border AI acquisitions.)

China's MiniMax, Zhipu AI beat OpenAI to IPO (Demonstrates the accelerating pace of AI commercialisation outside the US and shifting competitive dynamics.)

UK AI firm Faculty to be acquired by consulting giant Accenture (Reflects continued consolidation as major consultancies seek to bolster their AI capabilities.)

AI governance news

No 10 condemns 'insulting' move by X to restrict Grok AI image tool (Highlights escalating tensions between governments and AI platforms over access and content moderation policies.)

Yann LeCun: Meta 'fudged' on Llama 4 testing (A rare public critique from a leading AI scientist raising transparency concerns about benchmark reporting.)

Amazon's AI agents spark backlash from retailers after listing their products without permission (Reveals emerging friction points as autonomous AI agents interact with commercial ecosystems without explicit consent.)

Boffins probe commercial AI models, find Harry Potter (Provides new evidence on copyrighted material in training data, fuelling ongoing legal and ethical debates.)

OpenAI and kids' safety advocates team up on California ballot measure (Shows AI companies proactively engaging with regulation, particularly around vulnerable user protections.)

AI research news

From entropy to epiplexity: rethinking information for computationally bounded intelligence (Proposes a new theoretical framework for understanding AI cognition under real-world resource constraints.)

Everything is context: agentic file system abstraction for context engineering (Introduces novel approaches to managing context that could improve agentic AI systems' effectiveness.)

On the slow death of scaling by Sara Hooker (A significant critique examining diminishing returns from scaling, with implications for AI development strategy.)

Recursive language models (Explores architectural innovations that could enable more efficient and capable language model designs.)

LTX-2: efficient joint audio-visual foundation model (Advances multimodal AI capabilities with potential applications across media and accessibility.)

AI hardware news

Qualcomm debuts new chips for robots and Windows laptops (Expands edge AI compute options, enabling more sophisticated on-device AI applications.)

xAI plans third data centre, Musk claims will bring capacity up to almost 2GW (Underscores the staggering infrastructure investments now required to compete in frontier AI.)

Alphabet ramps up AI chip patents to curb Nvidia dependence (Reflects big tech's strategic push to reduce reliance on single hardware suppliers.)

AI to boost copper demand 50% by 2040, but more mines needed to ensure supply, S&P says (Highlights how AI growth is creating ripple effects across commodity markets and supply chains.)

Meta unveils sweeping nuclear-power plan to fuel its AI ambitions (Demonstrates how energy constraints are driving radical infrastructure decisions among AI leaders.)